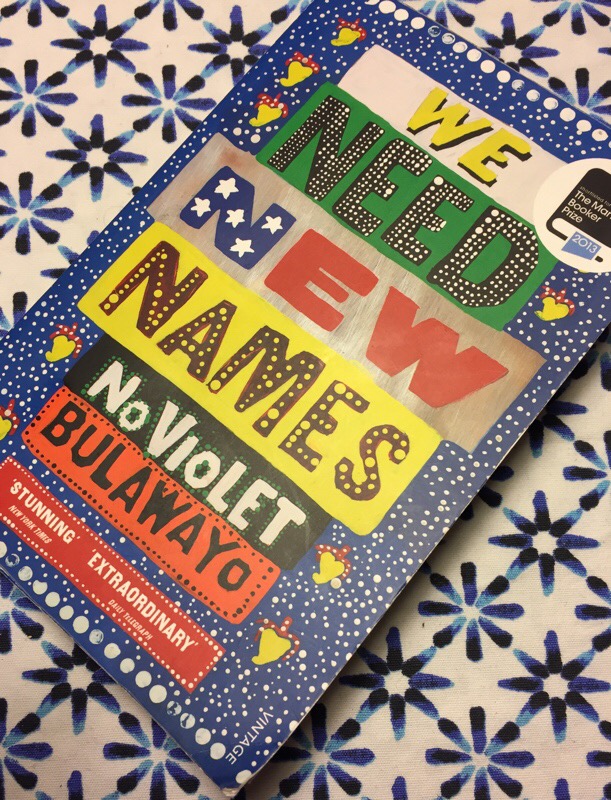

Book review: We need new names by Noviolet Bulawayo

Synopsis: Ten-year-old Darling has a choice:

it’s down, or out

In a shanty called Paradise, Darling and her friends spend their days stealing guavas and singing Lady Gaga, all while grasping at memories of life before and dreaming of escape – a dream that one day comes true for Darling. But, as Darling discovers, her new life in America is a far cry from what she imagined and this new world brings with it dangers of its own…

Publisher: Vintage Books

Pages: 290

Review:

I promise to be as spoiler free as possible and where I can’t, will put spoiler tags so that if you haven’t yet read it, you can skip forward.

Shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize in 2013, this book has been on my reading list for a while, so I’m glad that I’ve finally got off my butt and read it. Visually, the cover of the version I bought (there are two versions I found online) gives you a glimpse at what the book is about. The colours of the Zimbabwean flag dominating the words, with the American flag buried within it, suggesting to the reader first, the dominance of her home, the distant hope of a new life, and the internal struggle that Darling goes through over the years in defining who she is.

I should have started by saying that I enjoyed reading it. Noviolet’sstyle takes some getting used to as there are no quotation marks to indicate when people are having a conversation, so you work it out as you go along. Once you do, the dialogue flows quicker as you adjust to the ebb and flow.

The first half of the book deals with Darling’s life in Zimbabwe. Mostly with the days spent passing time with her friends Bastard, Stina, Sbho, Godknows and Chipo. We’re never told if Bastard and Godknows are those children’s real names. Even though this is Africa and I’ve heard my fair share of crazy names in Zambia, I’m not sure anyone would call their kids that. So yes, it distracted me a little. The Children witness a lot, almost too much, I felt, as though there was a need to cram everything into their experiences. Again, I’ve never lived in a shanty compound and can only imagine the complexity of life there but thus felt a bit crammed full of expectations of ‘things that happen in Africa’

From radical pastors, sexual abuse, suicide, freedom fighters, HIV, dealing with the mass emigration to South Africa, murder, unscrupulous white saviour NGOs, casual violence, abortion… I found myself wanting to say…come on, this is too much to happen to one child. But that may because I don’t want to believe it could happen to one child. That children can witness and be a part of, so much before they’re even teens.

But perhaps that was Noviolet’s intention. To make us say, “enough! Stop. This shouldn’t happen to children”

The simplicity with which this half of the book is written is heartbreaking. Huge events are glossed over with the blasé attitude of a child. Things that caught in my throats are ended with ‘we ran off and played’. It’s an effective tool that she uses well.

**spoiler tags**

In one scene the NGO people take photographs of the children and with a child’s innocence, they pose for the photos to be taken because they want ‘the gifts’ they are given after. Not seeing them for the charity they are and the cheap payoff they mean for PR photographs that will (probably) be used in ad campaigns far away from home.

‘They don’t care that we are embarrassed by our dirt and torn clothing, that we would prefer they didn’t do it; they just take the pictures anyway, take and take’.

**spoiler over**

This hurt profoundly.

I always wonder about content when I see the charity adverts on television. How can you agree to your photos being taken, to you being filmed, when it’s not an equal relationship; when you don’t fully appreciate what they will use it for, for years to come?

Anyway, I digress.

The second half of the book covers a number of years, a rapid change from the first half which gives the impression of a few on the by comparison. The scene moves to the United States where Datling has gone to live with her aunt. We are introduced to this new place but not with as much detail to the people. I felt rushed through it. Jumping from issue to issue chronicling various things that happen to Darling and before I’d got a sense of where she was, she’s moved to another city, another year, another part of growing up.

Again this works well in giving a sense of disoriented movement for an illegal expat who is still too young to appreciate what that means yet. The pull of home, that yearning for food from your own land, for language for weather, that is evident through the pages and I found myself thinking about home, the smell and taste of guavas, a lot. Damn I miss guavas!

And yet, it’s an experience I empathise with but couldn’t fully immerse myself in as I couldn’t relate to it. Things were rushed that I would have liked to know more about to sink into the book further. Why is her aunt so obsessed with fitness and weight and buying things? Why do we not learn more about TK, who seems a driving force towards the end, and yet we don’t really get to know while he’s around? And again it’s a tick tick of boxes of the western world: porn, low paid jobs, laughing at accents, never fitting in.

I liked the book, I just… I can see why it was shortlisted but I’d be hesitant to recommend it wholeheartedly to someone. There were just too many incidences of ticking boxes of what to cover in an African goes to America kind of way for me. And I especially didn’t like the non use of contractions, which is another stereotype thing I hate about the way people presume Africans speak as a whole.

Would I read it again? Yes. But not soon.

Should you read it? Yes, if only to view it against other modern day African writers.

I feel like I’ve been too harsh. But I really didn’t devour it at the rate I would a boon that I enjoy.

Recent Comments